Insights, clarity, action!

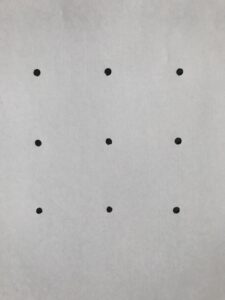

Ever heard of the nine dot puzzle? It’s a mathematical puzzle that challenges people to connect nine squarely arranged points in four (or less) straight lines, using a pen and without lifting the pen from the page (you can of course do it online, but the same rule applies – no lifting the ‘pen’ off the page).

I only came across the puzzle recently – I was googling the question ‘what does insight mean?’ – but it was apparently very popular among management consultants in the 1970s and 80s. If you haven’t come across it before, draw the above image on a piece of paper and have a quick go before reading on. Easy? Difficult? Obvious? Actually impossible? My 19 year old son, soon to be studying maths at uni, spent a good 20 minutes drawing and re-drawing lines before declaring it impossible and giving up.

‘Thinking outside the box’ is a pretty clichéd term these days, but it is what is required here (does the clue help you achieve those four straight lines, if you’re still trying?) The nine dot puzzle is also probably where the phrase came from (as someone who loves etiology, I am always pleased to learn the origins of a phrase or word, but that’s an aside…)

The puzzle demonstrates that thinking outside the box a) helps people to see challenges differently, enabling them to find the solution(s) they need and b) once a solution is found, it suddenly becomes glaringly obvious that that was the solution all along.

How often has that happened to you? You’ve toiled and toiled over a problem, even tried to look at it from different angles, but to no avail. And then something happens (you shift your perspective again or you ask a colleague for their input or you test a theory out…) and the solution presents itself – you have a Eureka! moment, gaining the insight you need.

Insight – a word that gets bandied around an awful lot in the business world. But how often do people really think about what the word means, to them or to others? I know what I mean by insight, but I was curious to find out more, so I looked up a couple of dictionary definitions. Being a word nerd, I love looking up dictionary definitions as well and will find any excuse…

Google’s Oxford Languages definition starts with: ‘the capacity to gain an accurate and deep intuitive understanding of a person or thing’. Merriam-Webster next: ‘the power or act of seeing into a situation’ or ‘the act or result of apprehending the inner nature of things or of seeing intuitively’. Then Cambridge Dictionary: ‘the ability to have a clear, deep, and sometimes sudden understanding of a complicated problem or situation’.

I prefer the last definition. The use of the word intuitive bothered me in the other two definitions because I think you have to be very careful about thinking about insight in terms of intuition. Intuition can lead us down the wrong path because it’s when we feel something is true. Unconscious bias, assumptions, gut reaction….Yes, we can intuitively know we’ve found the answer we were looking for, but I think it’s a very loaded word.

During my insights-gathering on ‘what is insight?’ Gestalt psychology came up several times.

The hallmark of insight, according to Gestalt theory, is its suddenness and clarity. People experience a sudden shift in understanding, often warranted by problem-solving accuracy

Gestalt’s Perspective on Insight: A Recap Based on Recent Behavioral and Neuroscientific Evidence

This resonates with the ‘sudden understanding of a complicated problem or situation’.

The research psychologist Gary Klein talks a lot about insight in his Ted talk The Light Bulb Moment.

He talks about making insights a habit, about being curious – if something unusual or unexpected crops up, give it your attention. Why is this happening? What’s driving it? What can I learn here and what do I need to do as a result? Don’t immediately dismiss the unusual or unexpected as an anomaly because you might be missing something.

And if something unusual or unexpected happens more than once – definitely don’t dismiss it. “Coincidences put us on the road to connections’ says Klein. Be interested in what he calls irritations, confusions and contradictions. And encourage others to do the same. Ask people what has surprised them at work this week. Ask yourself that question. In a world that is highly pressured and full of uncertainty, people look for certainty, when actually they should be investigating the uncertainties.

Klein talks about insights as unexpected discoveries. I like that – unexpected discoveries. I make a lot of unexpected discoveries when interviewing people, whether it’s for an article I’m writing or when conducting customer insights interviews. It is definitely those unexpected discoveries that lead to actionable insights that our customers can use to provide a better service to their customers, to hone their messaging to a certain audience, or any other challenges they need help with.

Let’s briefly look at this in L&D terms. Say a manager comes to you with a learning request – x needs to attend a course because y keeps happening. Do you just go with what the manager says and book x onto the course? Or do you dig deeper and find out why y keeps happening? You could come across an unexpected discovery that tells you a completely different learning intervention is needed. Or that it’s actually the manager who is the problem. Or maybe it’s a process or system failure. Whatever it is, you need to gain insight into the problem before coming to a solution.